Knife Information

Double Bevel Knife Sharpening — How to Do it Right

Double Bevel Knife Sharpening

Double bevel knives are incredibly versatile. They are one of the most commonly found knives in commercial kitchens and home kitchens alike. If you have ever been knife shopping at a homewares store, you have most likely only seen double bevel knives.

Simply put, they have an asymmetrical edge when looking down the knife, and knives are most often called “50/50” grinds, meaning the edge of the blade is shaped like the tip of a triangle. Double bevel knives can be very easy to sharpen with the correct technique and lots of practice, and if you follow these steps you’ll be push-cutting newspaper in no time.

1) The right whetstones.

Choosing the right whetstone for the job is critical in ensuring a satisfactory result. Usually for most knives, maintenance can be done with a 1000 Grit Whetstone. A whetstone with this grit will slowly remove microchips, and can be used for maintenance on a regular basis.

To polish the edge for increased sharpness, a higher grit stone can be used. The most common polishing grit for most knives is a 6000 Grit stone. The most popular grit in combination stones (a stone composed of 2 faces of separate grits) is the 1000/6000 Grit stone. However, most soft generic stainless steels will not perform well above 3000 grit. This is because the more you polish the steel, the less “toothy” the edge becomes, as you lose the micro serrations left by coarser stones.

For a knife that has larger chips, a lower grit (coarser) stone must be used first, in order to abrade the steel much quicker. We recommend a 280 or 500 grit to start, then progress to the 1000 Grit after this. Once you have the correct stone, let's make sure it’s in the right condition.

2) A flat stone is a happy stone.

As we are going to be pushing our knife up and down the length of the stone, the stone needs to be flat to achieve an even edge. Over time, a stone will wear out in particular areas (called “dishing”) and needs to be returned to a flat state to be effective. A flat blade on a dished stone simply won’t sharpen up as well as a flat stone.

This can be done cheaply with sandpaper and a flat surface, or much easier and quicker using the Atoma or similar style “Lapping Plate”.

For a worn out stone, draw horizontal and vertical gridlines about an inch apart. Place this side of the stone on a flat surface, onto the abrasive side of some sandpaper and abrade until the lines disappear. Alternatively, wet the stone after drawing the lines, place on a flat surface with gridlines facing up, and rub with the Atoma Plate until the lines disappear.

Some stones require soaking before use. Check the instructions with your stone or ask your retailer. Most stones benefit from 10 minutes of soaking in water. Do not permanently soak your stones.

Now that your stone is flat and prepared, we’re ready to sharpen.

3) The Correct Grip

For easy sharpening, we want to use what’s called a “pinch grip”, with your thumb on the side of the blade towards the heel, a finger down the spine, and locking your wrist and hand in place.

4) The Correct Angle

There are several different ways to ascertain the best sharpening angle, and this can be done using some angle guide clips or angle wedges. These are intended as guides, and should not be used beyond giving you an indication of the best angles to use. To begin, most Japanese knives are best sharpened at around 14-15 degrees.

5) Let’s begin!

Using your free hand, press with 2 fingers towards the tip of the blade. Place the knife on the wet surface of your stone closest to you. You want firm pressure, but not so much pressure that you can’t sustain an even angle when sharpening. Push in a long, even, steady stroke to the end of the stone. On the release of pressure at the top of your stroke, slide the knife back towards you in the same position. It is important to lock your arm, wrist, and hand to ensure your blade stays at the same angle the entire way through your sharpening strokes.

Repeat this motion while slowly walking your fingers down the blade unti you reach the heel after around 20 strokes per side.

6) The Burr

Perhaps the most important part of sharpening any knife is feeling for the burr. As you sharpen, you wear steel off the blade and fold this edge over to the other side, forming a small lip that you can actually feel. See if you can feel this burr forming on the opposite side of the blade. If you can’t, keep going with your sharpening until you can feel a pronounced, even burr the entire length of the blade.

7) Repeat for the back side

Follow the above steps for your opposite hand. If you’re now sharpening on your non-preferred side, don’t worry! You’ll soon become comfortable with practice, learn to lock your wrist, arm and hand and take it slow.

8) Progressing through the grits

Once you’ve achieved a strong burr on the opposite side, make one stroke on your initial sharpening side, this will centre the burr. You can now move up to your next grit.

9) Polishing & Burr Removal

Repeat this step on your higher grit stones, using slightly less pressure. Polishing does not require much force. To remove the remainder of the burr from the blade, you can run in softly through some cork, newspaper, or pass it over denim.

You should now be the owner of a very sharp knife!

Japanese Chef Knives - The Gyuto

When we talk about Japanese chef knives, the one you may be most familiar with is the Gyuto. Let’s dive into the origins and history of this tool, and the different ways you might use this world renowned chefs tool.

What Exactly Is It?

The Gyuto is the Japanese version of the western chef’s knife and is very versatile — it can be used for everything from chopping vegetables to slicing different kinds of meat.

Their length can range from between 18cm and 30cm, and usually have one long curve from heel to tip. This profile may vary slightly from region to region, as some blacksmiths prefer a taller Gyuto, some prefer a shorter height from heel to spine Regardless of the variations in profile, this slightly curved blade allows for many different styles of cutting.

The Origins And History

These blades emerged as a response to and inspired by western knives that Japan imported during the end of the 19th century, during the Meiji era.

The supply of these knives increased for two reasons after this period.

First, until this time Japan had sealed itself off from the world, meaning very little foreign culture and few foreign goods were allowed to enter Japan. When Japan began opening itself up, western-style chef’s knives flooded in along with European food culture. At this point, it became more common for people to start eating meat at dinner. The knife earned its name — Gyuto (literal translation meaning "cow sword") — because it was mainly used for cutting beef during the rise in meat-eating.

The second reason these knives were produced is because swords traditionally made by were no longer in great demand. While they still produced katanas and other weapons, blacksmiths turned to making kitchen knives as their rise in popularity proved to be an increasingly lucrative trade.

Using a Gyuto

Just like a western-style chef’s knife, it is ideal for a range of different tasks, and can be used a few different ways.

Rock-chopping: With a firm grip on the handle, begin your cut with the tip of the blade, and without lifting the knife off the board, contact the blade with the board all the way down to the heel, sliding the blade forward as you cut. Repeat this motion by lifting the heel of the blade in the air and rocking back and forth along the blade length.

Pull-cutting: Start with the heel of the blade the back of your produce, contact the blade to the board from heel to tip, slicing through your produce. Great technique for proteins.

Push-cutting: With the blade parallel to and off the cutting board, using the flatter part of the blade toward the heel, push down and forward at a 45 degree angle. Once pushed through your produce and contact with the board is made, pull up and back in the same direction and repeat.

The tip area, being nimble and small, makes it excellent for piercing tough meat and making fine cuts.

The blade length varies based on what you are likely to use it for. Shorter Gyuto are are more nimble but long blades give you more blade area for larger cuts of meat or vegetables.

Final Thoughts

Rich in culture and history, the Gyuto knife would be a great addition to any kitchen if you’re interested in upping your home-cooking game.

We consider it to be the first knife in your collection, as it can handle almost all manner of tasks. Opt for a 180mm-210mm if you prefer a smallish blade, or choose a 240mm blade if you prefer much longer knives for your tasks.

Whether you’re a home cook, amateur chef or a professional, we all need a good set of knives in the kitchen.

For many chefs it’s what defines them, and a Japanese chef knife arguably is as good as it gets. Working with the right blade will ensure superior precision and maintain the integrity of the ingredients you’re working with.

Japanese chef knives are becoming increasingly popular with Western chefs, and it’s not surprising given their rich history and reputation for quality, sharpness and overall precision craftsmanship.

At Chefs Edge we specialise in high performance Japanese kitchen knives crafted by some of Japan’s most talented blacksmiths. We only pursue kitchen knives of the highest quality and the finest craftsmanship, and provide them to you at the best possible price, while striving to deliver the best customer service possible.

If you’re considering Japanese chef knives for your kitchen, it’s important to first understand the different kinds, to help you decide what’s right for you. The types of kitchen knives you need will ultimately depend on your level and style of cooking, and the techniques you’ll demand from your knife.

Gyuto

If you’ve never owned a Japanese kitchen knife before, the Gyuto meaning ‘beef knife’ is the most versatile choice to start your collection and obsession! One of the most commonly used knives in the kitchen, the Gyuto can cover a majority of kitchen tasks.

It’s similar to a classic Western style chef’s knife, except that it’s typically lighter and thinner. The Gytuo is typically anywhere between 18cm-27cm in length, depending on the required task. It has a long curve from heel to point and is ideal for rocking-cuts and precision work like mincing, fine preparation of vegetables and slicing meat.

Shop our range of Gyuto’s here

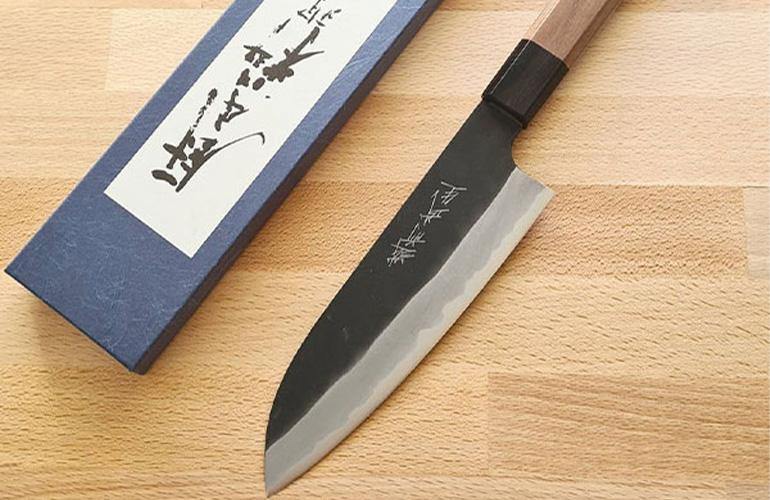

Santoku

If you’re looking for another good all-rounder, a Santoku knife is your next best choice after the Gyuto. This smaller multipurpose knife has a flatter blade profile that the Gyuto, and is great for dicing and chopping vegetables, fish and meat.

The broader blade also helps to scoop ingredients off the board with ease. The Santoku can range from 13cm to 18cm in length, and has a slightly flatter cutting edge than the Gyuto.

Shop our range of Santoku’s here

Bunka

A versatile blend of the Santoku, Gyuto, and Nakiri, the Bunka is a smaller and thinner than the Gyuto and Santoku, with a much higher taller blade, and a ‘K-tip’ which allows more specialised cutting tasks.

This general purpose knife is also ideal for push cutting and chopping vegetables, and can handle delicate work like trimming and paring with ease. (Plus, they look absolutely fantastic, our favourite blade shape by far!)

Shop our range of Bunka’s here

Deba

For Western Chef’s the Deba is the ultimate butcher’s knife alongside the trusty meat cleaver. Although the Deba is traditionally known for its uses in filleting fish, its structure merits its use for cutting through joints of meat and poultry.

You’ll notice that an authentic Japanese Deba will have a single bevel edge, while the Western version has a double bevel edge, which is why it’s also ideal in meat preparation.

The Deba has a thick spine, and is usually heavier than it’s Gyuto/Santoku counterparts. This extra weight helps make light work of more heavy duty cutting tasks.

Nakiri

As its meaning suggests, the Nakiri knife is a vegetable knife. Crafted with a straight double edged blade and no tip, it’s perfect for chopping and dicing.

You’ll find this knife to be everyone’s ‘go to’ in most Japanese homes. The flatter blade profile allows more of the cutting edge to be in contact with the board.

Shop our range of Nakiri’s here

Petty

The Japanese version of a French petit knife, the Petty knife is the quintessential paring and utility knife.

It’s nimble and perfect for small handheld tasks that the Gyuto or Santoku is too large for, such as peeling and cutting small fruit, vegetables and herbs. The small length of the blade makes sharpening a breeze compared to other types of knives.

Shop our range of Petty’s here

Yanagiba

The original sushi knife! Traditionally used to cut sashimi, but these days can also be used to cut meat. This is a long, thin blade up to ~37cm in length, and is a single bevel, chisel ground edge. This ensures the meat falls off to one side and repeated cuts can be made to large pieces of meat in quick succession with excellent repeatability.

Other types of Japanese kitchen knives

Chukabocho – the Japanese version of a cleaver, it is large and rectangular in shape and great for preparing large veggies such as cabbage. The thin blade also means it can handle delicate tasks like trimming and mincing herbs. This cleaver is not designed to be used as a meat cleaver.

Pankiri – a serrated bread knife, only used for slicing bread and baked goods.

Usuba – a vegetable knife with a Kataba blade. This knife is a little more difficult to use than a Nakiri, but its shape and sharpness ensures a clean and crisp cut every time.

Whether it’s slicing and dicing, chopping or carving, you’ll find the perfect workhorse in the kitchen with a Japanese kitchen knife. If you need help deciding on what knife will best suit your needs, get in touch with the team at Chefs Edge. Once you’ve got your hands on a Japanese kitchen knife you’ll never look back!

Why Japanese Knives Australia?

Take a dive into the wonderful world of Japanese chef knives, and why they’re considered to be the best in the world.

There is a certain romanticism associated with fine goods that are crafted by hand. Japanese chef knives are forged with precision and care, steeped in tradition, and hold quality of the finished product above all else. They hold a special place in the hearts of many.

Deep down we yearn to own something special, something that has been meticulously designed and constructed, not stamped out on an assembly line.

Yes, they can be pricey, the price reflects the caliber of the build. A high-quality knife, with the correct care, will remain are the forefront of your kitchenware for years. Not only do they make light work of dicing onions, Japanese kitchen knives have numerous design features that make them outperform almost all other kitchen knives in the world.

So what makes Japanese kitchen knives so special?

Weight

Generally speaking European knives are heavy; this is due to the ‘full tang’ design feature. The steel of full tang blades continue through to the end of the handle, as pictured below.

In some instances, the handle is also made of steel resulting in a knife which is overly heavy and cumbersome to use for long periods of time. As seen in the image below (courtesy of www.thespruceeats.com), all that extra steel in the handle adds much to the weight of the knife.

The steel of a Japanese blade quickly tapers off in size after it enters the handle reducing the overall weight of the knife. This may bring the balance of the knife to be slightly forward heavy, a trait many chefs quickly get used to in order to take advantage of the Japanese chef knives superior performance. This image below shows an average Japanese chef knife in terms of the steel quickly dropping off as it gets into the handle.

Some Japanese chef knives may feature what is called a ‘distal taper’, where the thickness of the blade increases just before it enters the handle, adding weight to the rear of the knife to bring it back into balance. This increases comfort to the user making it perfect for all day every day use.

Grind/Bevel

The ‘grind’ or ‘bevel’ refers to the shape of the blade when you look down from the handle to the tip. On the whole, European knives have a thicker, heavier blade and the cutting edge itself is a short ~ 20-degree taper that is even on both sides (50/50), about 1-2mm from the tip of the blade.

The Japanese blade will be much thinner, and the thinner the blade, the easier cuts are made, and the more agile cutting work it can perform. The cutting edge of a regular Japanese knife is much lower than 20 degrees and starts much higher on the blade. Traditional Sashimi knives like the Yanagiba or the Sujuhiki (knives designed for long pull cuts) have only a single bevel, meaning that one side is flat, and the other side tapers off at a low angle. This pushes the food away from the blade once the cut has been made.

A thinner grind, although resulting in much greater sharpness, means that a Japanese kitchen knife may be prone to chipping or breakage if used improperly (torquing/twisting the blade while cutting, or hitting or chopping hard or frozen objects). Whilst European knives can be more robust, they are made of softer steel, go blunt quicker, and can’t make as precise cuts.

For most chefs, the trade-off for much better all-round performance is worth the small level of extra care and maintenance required of Japanese kitchen knives.

Exotic Steels

While many European knives will be made from some form of softer stainless steel, most Japanese knives employ the use of high-carbon steel combined with extra elements (nickel, chromium, vanadium, tungsten, molybdenum) to produce exotic alloys that have greatly enhanced corrosion resistance, hardness, and durability.

A Japanese traditional high-carbon steel such as Aogami Super (Blue Paper Steel) or Shirogami Steel (White Paper Steel) will not have the corrosion resistance of their stainless counterparts, and as such will need extra care and maintenance and can be reactive to certain foods, developing a multicoloured hue on the blade known as a ‘patina’.

It is common for Japanese knives to be crafted with a technique called ‘San-Mai’, by which a very hard cutting edge of reactive, high-carbon steel is sandwiched between 2 external layers of softer stainless steel. This guarantees fantastic cutting performance and an easy to maintain blade.

Hardness

Steel hardness can be graded by the Rockwell hardness scale. Softer steels such as Cromova can only be hardened to 54-56 which is considered quite low. These knives can take more punishment, and are less brittle, but will go blunt extremely quickly due to their softness.

Japanese knives are normally anywhere between 61-67 HRC, giving them their legendary edge retention and long lasting sharpness. This comes at a price, however, with extreme hardness comes the risk of chipping and damaging the blade from improper use as described above.

Tradition and Care

The Japanese consistently strive towards excellence in their craft, as is the age-old philosophy so widespread in Japanese culture. Individual Blacksmiths will always be creatively exploring ways to refine their processes and push the boundaries of what is possible in knifemaking, whilst preserving the traditions that have been passed on throughout generations.

Their aim is to ensure that every blade is as carefully and meticulously crafted to the same quality as the last and that the lust for Japanese kitchen knives, the finest in the world, continues for many more generations to come.

A Guide to Japanese Knives (2021)

A Guide to Japanese Knives

In the culinary world, Japanese knives are highly praised. We're here to tell you that they truly live up to the hype. Japanese knives are the product of a rich culture. Skilled artisans use the finest materials and techniques to make these high-quality tools. Many varieties are available that serve different purposes in the kitchen.

Looking to add Japanese knives to your arsenal? We don't blame you. These tools make a great addition to your kitchen. They also go a long way in helping you prepare authentic cuisine.

Not sure how to find the right Japanese knife in Australia? You're not alone. It can be tricky when you're not familiar with these traditional tools. Luckily, we're here to help!

Here's a complete guide to Japanese knives. We'll go over different materials, varieties, and more to help you become an informed buyer.

Western vs. Japanese Knives

Before diving in, it's worth mentioning the main differences between Western and Japanese knives.

Material Quality

Western knives are easier to care for. They aren't as brittle and won't rust as easily. Their Japanese counterparts require more care as they are more brittle and prone to rust. However, they tend to be sharper and hold their edge longer.

Blade Shape

Traditional Japanese knives have a single-bevelled blade, where one side is sharpened, and the other side is completely flat. A chef uses this blade to make precise diagonal cuts. Note that because just one side of the blade is sharpened, a single-bevelled knife is made for right-handed chefs. If you are left-handed, you will have to get a specialty leftie knife (which can be more expensive).

Western knives, on the other hand, usually have double-bevelled blades. They are sharpened on both sides, resulting in a V-shaped blade edge. Though easier to sharpen, this blade isn't as good for high-precision cuts. But, you'll be glad to hear that double-bevelled blades are ambidextrous by design. Both left- and right-handed chefs can use them with ease.

Know the Different Materials

Now, let's take a look at the different materials Japanese knives are made out of.

Carbon Steel

Relatively speaking, carbon steel is sharper and less resistant to wear. When it does become dull, it's easier to sharpen.

Carbon steel is also more brittle and prone to rust. Professional chefs are more likely to own carbon steel knives to keep up with the required maintenance.

Stainless Steel

Compared to carbon steel, stainless steel isn't as sharp. As a result, it is prone to wear and slightly more difficult to sharpen.

Stainless steel, however, has many perks. It is easier to care for as it isn't as brittle or prone to rust. This makes it a popular choice among amateur chefs.

Different grades of stainless steel knives (VG-10, 10A, or AUS-10, etc.) offer unique hardness and edge retention levels.

Damascus Steel

Traditional Damascus steel is no longer made. Modern manufacturers, however, attempt to replicate the historical material.

Damascus steel knives can be made out of either carbon or stainless steel. Their key feature is their beautiful water-like patterns. Many chefs prefer knives made out of this material for aesthetic reasons.

If you are buying a Japanese knife in Australia, consider whether you want a carbon or stainless steel knife. Then, decide if you want a standard design or a beautiful Damascus pattern.

Find the Right Japanese Knife in Australia

The type of material you choose is important. However, you'll also want to find a knife of the right size and shape for what you'll be using it for.

Here are some of the most popular types of Japanese knives:

Gyuto

A Gyuto is not necessarily a traditional Japanese knife. It is a Japanese adaptation of the Western chef's knife.

A Gyuto has a curved blade, tall heel, and pointed tip. Its blade is usually around 210-270mm in length. While chefs use it for various applications, a Gyuto is particularly useful for piercing and rocking motions.

Garasuki

A Garasuki is another Japanese adaptation. It mimics a Western boning knife.

The triangular blade is tough and has a sharp tip. While not good for cutting through bones, it is great for maneuvering around tight spaces. Chefs often use it to break down poultry and red meat.

Honesuki

A Honesuki is essentially a smaller version of a Garasuki.

Santoku

A Santoku (along with the rest of the knives we'll be discussing) is a traditional Japanese knife.

A Santoku is similar to a Gyuto in that it is all-purpose. The name, translating to “three virtues,” refers to its ability to cut meat, fish, and vegetables. With a Santoku, chefs tend to use an up-and-down motion rather than a rocking motion.

Nakiri

A Nakiri is for cutting, slicing, and peeling vegetables. The double-bevelled blade, which can be between 240-300mm, is thin and straight.

Usuba

An Usuba is the single-bevelled version of a Nakiri. Its blade is much thinner, making it perfect for decorative cuts and paper-thin slices.

Takohiki

Chefs use a Takohiki to slice raw fish for sashimi. The blade is rectangular.

Yanagiba

A Yanagiba is also used to slice raw fish for sashimi. The blade, however, is slim, long, and has a curved tip.

Deba

A Deba is for breaking down fish. The chunky blade can cut through bones, descale, etc. A standard size Deba (Hondeba) has a blade length of 210mm.

Unagisaki

A Unagisaki is for preparing Unagi. The sharp tip can pierce through the slippery eel's skin and filet the fish.

Menkiri

Chefs use a Menkiri to cut through soba noodles and udon. A Menkiri is heavy, has a straight edge, and features a blade that extends to the handle.

Buy Your Japanese Knife in Australia

With the help of this guide, you should find the perfect Japanese knife in Australia. Just keep in mind that these knives are crafted with care, and you'll need to keep them in pristine condition if you want to get your money's worth.

How to Make a Japanese Knife

Many people have a deep and entirely justifiable fascination with Japanese knives. Sharpness is part of the intrigue: learn more about the history of tameshigiri, if you want proof of the power of these blades.

There's also a fascinating background of how Japanese knives are made. A certain part of the forging process can only be performed after dark so that the blacksmith can better judge what color the metal is glowing — you've got to admit that's unique.

But aside from intrigue, people love the quality of these knives, thanks to how they're made. Here, we look at the process that Japanese knives are put through to obtain that incredible quality. Let's start with a breakdown of how they differ from Western knives.

What's the Difference Between Japanese Knives and Western Knives?

There are a few major differences between many Japanese knives and Western knives:

Single bevel (Japanese) vs. double bevel (Western): the single bevel means that a blade is better suited to one hand than the other and can hold a sharper edge for more delicate cuts

Harder, more brittle steel: Japanese knives tend to be made of harder steel. This is more brittle but holds an edge for longer if treated with respect.

Single-piece vs. composite handle: Western knives tend to have a handle made of two pieces of wood riveted together around the tang. In Japan, the tang is traditionally knocked into a single block of wood.

So, it's clear Western and Japanese knives are very different, but how are these blades made? There are numerous production modes, but we'll just look at two: the high-quality factory method and the mysterious, romantic hand-forged method.

How to Make a Japanese Knife in the Factory

Rest assured that this isn't your typical ‘factory-made’ knife. There may be a team of workers and machinery, but the care that goes into forging these knives is still exquisite. It starts, of course, with the metal.

Step 1: Initial Shaping

Blanks of metal are heated in a forge and then pounded out with a power hammer. The metal is then periodically quenched to give it strength. This process leads to the blades taking on their basic form and achieve uniform strength in all parts.

At the end of the shaping, the blades are treated on a sanding belt. The shape of the blades is controlled and carefully monitored by expert craftspeople. As mentioned, this isn't your typical factory.

Step 2: The Kiln

The knives are put into a kiln and then cooled at a controlled pace a day after the initial shaping. The heating and cooling changes the metal's molecular structure to something approaching the desired result — but not quite. There's more work to be done on day 3.

Step 3: The Finished Shape

As the knives aren't yet at the final hardness, the final stage is to make some cold adjustments. This is an intensive, meticulous process done by hand. The knives are given their desired shape and then put through the kiln one more time, which gives them the perfect hardness.

Step 4: Sharpening

Sharpening a knife is a specialized job. The blades are sent to experts who sharpen the blades to an unbelievably fine grade. Even here, the temperature is key: the wheels that sharpen the blades are kept cool with water, as raising the metal to high temperatures would compromise its quality.

The knives produced using this method are sharper and of better quality than what you'll find in many restaurants. Here's what you wanted, though: the handmade method.

How to Make a Japanese Knife by Hand

Step 1: The Furnace

Masters in forging Japanese knives also start by heating metal in a furnace. So far, so familiar. Just like a great chef knows when a steak is perfectly medium-rare by touch, a master blacksmith knows when the metal is hot enough by its color, as well as other signals that the untrained eye just won't notice.

The metal is shaped with an air hammer and the watchful eye of the blacksmith. Precision is the key to perfection here, and not a single blow is wasted.

Step 2: Cold Forging

‘Cold forging’ means that the metal is, well, almost cold. This makes it far harder to work with than hot metal but yields far superior results. If you don't know what you're doing, it's easy to damage the metal by cold forging.

The blacksmith cold forges the knife to make the metal stronger on a molecular level than if it was hot forged. This job is sometimes given to a master craftsman's apprentice, which can seem an odd term for someone who already understands metalworking better than most mortals.

Step 3: Quenching

The blade is heated and then quenched to bring it to a desired level of hardness. Such is the need for perfection that it's important to use the right fuel for the furnace.

Coal, for example, contains a lot of impurities that make it unsuitable for this refined process. Think of your dad's bourbon-soaked hickory wood chips for his beloved barbecue, but on a whole different level.

The blacksmith knows instinctively what color the metal's glow has to be. This is why quenching only takes place after dark.

Step 4: Tempering

The blade must then be tempered to achieve the final, desired hardness. This takes place in carefully controlled temperature conditions and is essential before the blade can be sent off for sharpening.

Step 5: Creating a Legendary Edge

A top-quality, hand-forged knife deserves no less than the best to put an edge on it. A master knife sharpener is known as a togishi. This person's job is to put an edge on the blade that matches the quality of its construction.

A Labor of Love

Japanese knives are works of art in their own right. The care and years of training that go into producing a quality knife are formidable, and this is true of specialized factories and hand-crafted knives.

If you're interested in Japanese knives, something you might want to put on your bucket list is taking a tour of a workshop. Japanese knives also make wonderful gifts, as each one has a story behind it. Let your fascination take you further into this amazing world: ask any ‘apprentice.’ There's always more to learn!

Choosing The Right Chef Knife For You

Never heard of a Gyuto? No idea what SG2/R2 is? Double or Single Bevel? Don’t panic, we’ll explain what you need to know when picking out a Japanese Chef knife.

If you’re in the market to purchase a Japanese kitchen knife, you might be looking for a timeless, meaningful gift, interested in the culinary arts, a chef, or simply wanting to cook a delicious meal for your loved ones.

There are many different Japanese knives, so much so it can be a little overwhelming to make a choice. Here, we cover a few main points to consider when choosing the right Japanese chef knife for you.

Blacksmith

Taking the maker of your knife into account can give you an idea of the overall quality you will be receiving. The manufacturer will influence the design, balance, performance, and price of the knife.

Different blacksmiths will also prefer to use particular steel, which may have some benefits over other knife steels available. As the craft of knifemaking is a traditional art form passed down through generations, it is something Japanese blacksmiths hold very dear.

Through the application of these varying techniques, each blacksmith continues the traditions of their forefathers, producing a knife that is unique to that families history, a culmination of (sometimes) hundreds of years of tradition. Some people prefer to have matching sets from one blacksmith, while others do not mind mixing and matching different blacksmiths to create a set that they are happy with. This is personal preference.

Style

The style of knife you buy depends largely on what you’re looking to do with it and what you are preparing. Whether you’re preparing sushi or peeling vegetables, the process of chopping and slicing is very different and a different knife will be required.

Make sure you know how you are primarily looking to use the knife so you can select the correct style. A home cook that would just like to own a high-performance knife might lean towards a Santoku between 160-180mm, whereas a professional chef with a wide variety of tasks to complete may opt for a Gyuto of 210mm length or more, and a petty or small utility knife to cover the smaller tasks at hand.

Blade Material/Steel Combinations

We could write an entire article just about this! (In fact, we might just do that!) The type of steel used in a Japanese chef knife may not seem overly important, (as long as it’s sharp, right?)

Not quite!

The blade material will impact many things; how long your knife lasts, how easy it is to sharpen, the overall look, and more. You may consider getting a knife made of the simpler AUS8, Molybdenum Vanadium, or VG1 steels if you are just entering into this market and feel overwhelmed by the choice. This type of knife is more chip resistant and a little tougher than other options.

If you’re a more advanced user of knives and you’re comfortable putting more care and effort into them, consider using some of the higher hardness, more complex stainless steels like VG10, R2/SG2, SRS-15, AEB-L, HAP40 or ZDP-189.

Then you must consider the carbon steels. They have a higher maintenance requirement, but they can be used by all skillsets. Most Japanese blacksmiths will prefer to use the traditional Japanese chef knife steels, made by Hitachi Metals. These are the White Paper Steels (Shirogami), Blue Paper Steels (Aogami). There are some slight variations of Blue and White paper steels, but they are essentially about as close to the samurai sword steels of hundreds of years ago we have today.

They are high in carbon content, resulting in the steel being harder than almost all other knife making steels, ensuring they will stay sharper for longer.

They are, however, what is called ‘reactive steel’. This means they will oxidize (rust) and form a ‘patina’ (a discolouration of the steel) and also develop rust spots if they are not kept dry between uses.

In some cases, 15 minutes left wet will be all it takes to form early rust spots. This is avoided by proper care and maintenance, but also by a blade construction technique called ‘san-mai’, which uses a core or cutting edge of high carbon steel, with a softer stainless steel clad on either side. This results in exceptional performance with minimal maintenance.

Size

A larger knife generally means you can perform more work with it, however, your workspace should also then need to accommodate a larger knife. The knife you purchase should not be longer than your cutting board is wide.

That being said, you don’t want your knife to be too small, or too large to perform everyday tasks. A general purpose knife for most like a Santoku of 160-180mm is, therefore, a great place to start. Once your Santoku becomes either too large or too small, it’s time to expand! Look for petty knives around 100mm for smaller delicate tasks, and Gyuto’s up to 240-300mm for larger tasks like carving meats, but beware of bones!

Handle Material/Shape

The handle material may impact how you grip the knife, how sturdy the knife feels as you use it, as well as the appearance of the knife.

A steel handle, a feature of many western knives may slip or not feel as comfortable in the hand and a timber handle crafted into the shape of an octagon. The octagon handle shape is one of the marks of a traditional japanese chef knife, as it allows the edges of the octagon to fit into the grooves of the fingers once the handle is grasped in the hand.

Chefs Edge has a preference towards the octagon handle, and as such we partner with craftsman worldwide to create stunning unique handles made from exotic timbers.

Bevel Angle Ratio

The traditional Japanese chef knives (Yanagiba, Sujihiki, Deba etc) are designed to have a single bevel. This one-sided bevel angle is perfect for sashimi slicing, but is not well suited to everyday cooking at home or in a professional kitchen for general use.

The Japanese blacksmiths have realized this, and almost always craft the Gyuto/Santoku/Nakiri/Bunka with an even 50:50 bevel to accommodate the western chef with a varied set of kitchen tasks.

HRC

The HRC of a knife refers Rockwell Hardness Scale. A knife with a higher HRC, in general, will retain its edge for longer, but can be more brittle.

This is why a Japanese chef knife should never be used to chop bones, frozen objects, or hard foods (sometimes a big sweet potato is a no no!) It’s also important to remember that not all steels behave the same at higher hardness, and higher hardness is not the sole determining factor of knife performance.

Just because something has a high HRC rating doesn’t make it a better knife. A regular European chef knife made from a softer steel may be hardened to 55-56 HRC, but a Japanese knife made from Aogami Super or ZDP-189 may be hardened anywhere up to 67-68 HRC.

At the end of the day, there are a wide number of factors to take into account when choosing the right knife for you. If you get stuck, please don’t hesitate to get in touch by any of the channels on our website, or send us an email to info@chefs-edge.com.au!